DESIGNING PHYSICAL INTERFACES:

interacting with our world

May 31 - June 9, 2004

instructors: eric forman & cynthia lawson

LECTURE 3: PROGRAMMING THE BX-24

WRITING BASIC PROGRAMS FOR THE BX-24

- Free BasicX software from Netmedia (download from http://www.basicx.com)

- Program editor

- Project manager

- Debugger

- Compiler

- Downloader

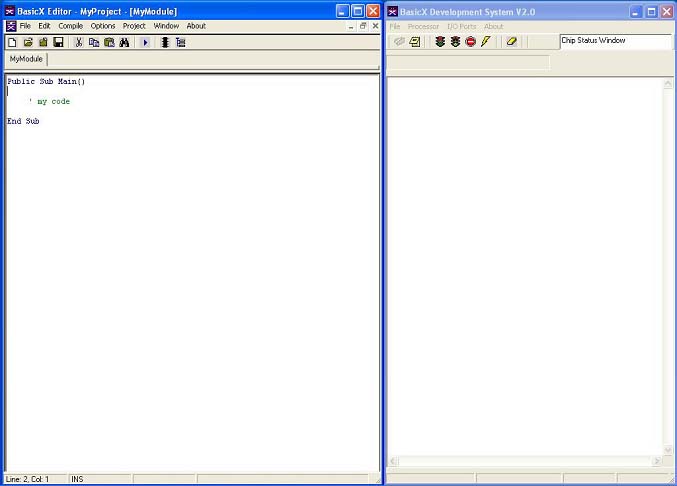

- Programming Environment

- Program Editor (Left)

- Downloader/debugger (Right)

This software is easy to use and free. It has a few peculiarities, however, sometimes requiring full system restarts.

You will need to tell it which serial ports you are using for programming and debugging (what they call “monitor”) by setting the Download Port and Monitor Port numbers under the I/O Ports pull-down menu in the Downloader/Debugger window.

- Basic

- Very close to Visual Basic

- Has standard programming features

- If-Then statements

- For-Next loops

- Subroutines and functions

- Program is compiled before being sent to chip

- This translates it to lower level language

- Programs are called modules

- Projects can contain multiple modules

- Projects called projectname.bxp

- Modules called modulename.bas (The code you write is saved in the modulename.bas file. It is just a text file. This is the only file you really need if you want to copy a program to another computer, or back it up to disk.)

- Don’t worry about other files for now

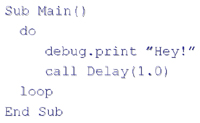

- Programming Examples

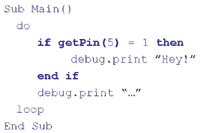

- BASIC SYNTAX

- This code just causes the text “Hey!” to appear over and over in the BasicX debugger window on your computer screen.

- Every block of code must be enclosed in a subroutine.

- Every program’s first subroutine must be called Main.

- Debug.print sends a message through the programming cable in serial ASCII format, which the BasicX debugger displays on screen as text.

- Delay is one of many built in functions, it waits a given number of seconds.

- Almost every program on a microcontroller will use an infinite loop so that it runs the program endlessly.

- To call one of your own subroutines, use Call yourSub().

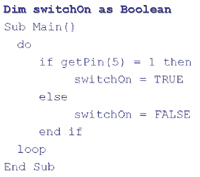

- IF THEN, GETPIN

- getPin() reads the voltage level on the specified pin and translates it to a binary value, either 0 or 1.

- If there were a switch wired to pin 5, this program would output “Hey!” over the serial port as fast as possible while the switch was turned on.

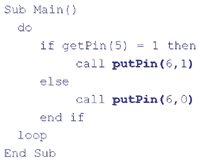

- PUTPIN

- putPin() outputs voltage on a given pin, either 0 volts (also called binary 0 [zero] or “low”) or +5 volts (also called binary 1 [one] or “high”). The syntax is Call putPin(pin,state).

- Else executes statements only if the initial If condition is not true.

- If an LED lamp were connected to pin 6, and a switch were connected to pin 5, the switch would turn the LED on and off.

- VARIABLES, DATA TYPES

- Boolean: TRUE or FALSE

- Byte: 0 to 255

- Integer: -32768 to 32767

- Long: -2147483648 to 2147483647

- Single: -3.402823e+38 to 3.402823e+38

- Single is also referred to as float, or floating point or

decimal-point numbers

- Single is also referred to as float, or floating point or

decimal-point numbers

- String: 0 to 64 characters

- Each data type takes up different amounts of memory. Conserving memory by assigning data types becomes important when your programs get longer and more complex.

- Data type memory usage:

Boolean, Byte 1 Byte

Integer 2 Bytes

Long, Single 4 Bytes

String 2 Bytes + 1 Byte per char -

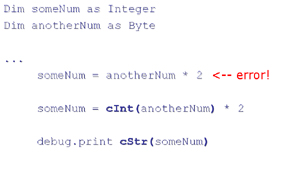

The requirement that variable data types agree is one of those little things you have to put up with when using most microcontrollers. These kinds of corner cutting is what allow such powerful features to be packed into such tiny packages.

- Data type must be declared

- Memory space is limited

- Unlike computers

- You won’t have to worry at first

- Types must agree

- Compiler error if they don’t

- Conversion functions get around this

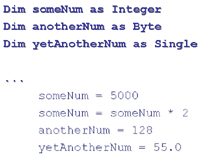

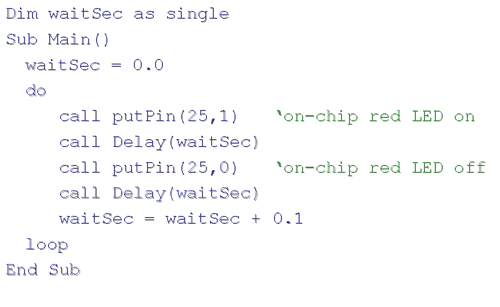

- Sample Code:

- Variables are declared with the Dim statement. Dim is short for “dimension,” because it tells the compiler how much memory space to reserve for the variable.

- Variables can be either local or global. Local variables are only visible within the block of code (subroutine or function) they appear in. Global variables are visible everywhere. Usually all variables are global except for temporary variables like loop counters.

- Note that variables of type Single always need the decimal point.

- Type Conversions:

Remember, you can’t do operations with different data types. You must convert one of the variables to the other’s type.Here, debug.print sends ASCII values of digits in variable someNum over the serial port. So if someNum = 256, the characters “2,” “5,” and “6” would be sent, causing “256” to appear in the debug window on your computer.

See system library in BasicX documentation for all conversion functions.

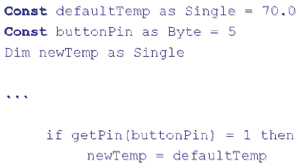

- Constants

Constants can be declared as any data type. Operations with constants, as with all variables, must use same data types.

Pin assignments can be declared as byte constants - this can make your code much easier to read and allows easy wiring changes.

- Sample Program

Pins 25 and 26 refers to the tiny LED’s built on to the BX-24. 25 = red, 26 = green. They are useful to turn on in your code so you know your program is working before getting mired in other debugging steps.